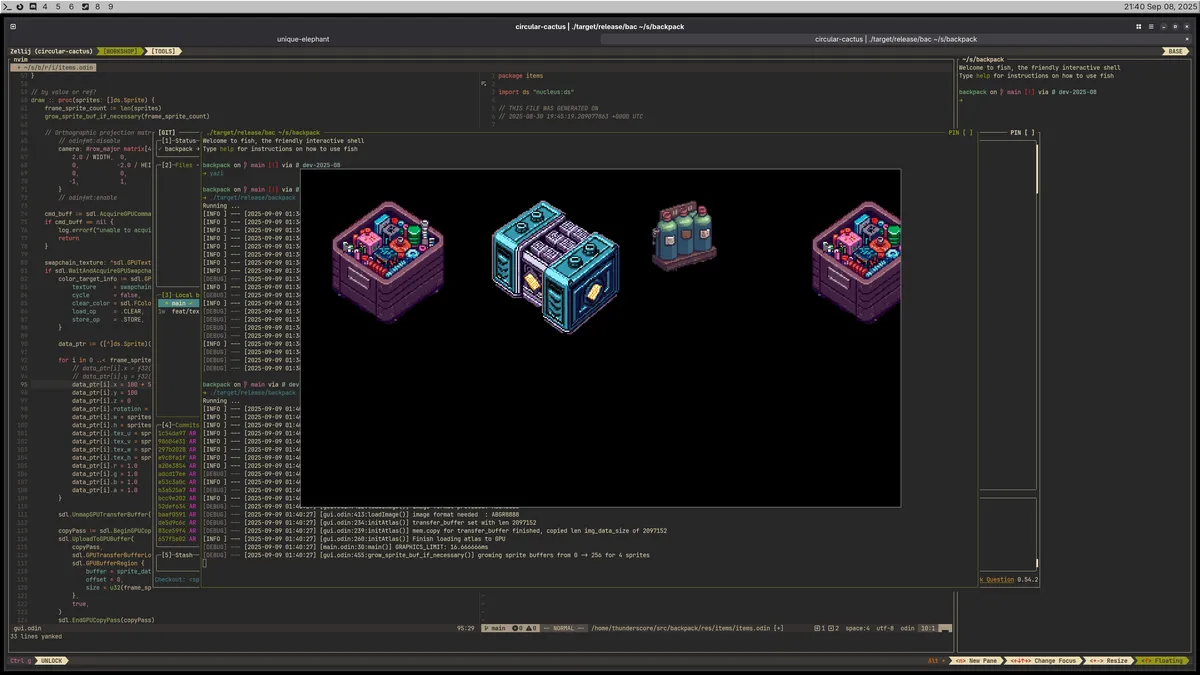

devlog0: Initial Commit

MID MAI - END OF AUGUST

I started making a toy game engine in Odin as an excuse to learn how to manage memory manually. I originally planned to do 30 consecutive no-zero days. It kind of fizzled out after the first two weeks. The remaining days spread out over the rest of summer.

It took just over 35 days of work, some of them for 4h, but most of them less than 1h, to complete my original 30 days estimate.

| Window | 🗸 |

| Texture Graphic Pipeline | 🗸 |

| Build Pipeline | 🗸 |

| Texture Packing | 🗸 |

Background

Most of my paid labor has been in web and mobile for the last 10 years. I had a short stint in game development as well, but not long enough to get a good grasp of most verticals in that realm. I come to this project with lots of programming experience, but almost none relevant to this problem space.

I am not looking to ship a game. I am not looking to learn specific black boxes and frameworks. I am here to learn and understand the whole stack. With that in mind, I've chosen to work in Odin, a low level language pitched as a C replacement with batteries included for common patterns like maps, strings, and temporary allocators. The support for interoperability with C libraries felt well-thought-out from my limited experience with it. The syntax looks fine, and the rationale behind the tradeoffs chosen while making the language speaks to me more than those of Zig and Nim. Odin's low popularity makes for sparser documentation and resources, but one can reach a helpful community of the language users on Discord and have access to a trove of idiomatic examples on GitHub.

Game Engine

At its core, a game engine is nothing fancy. A for loop on each subsystems that makes a game:

main :: proc() {

for {

handle_input() // not implemented

game_logic() // not implemented

ai() // not implemented

some_other_stuff()

render_frame()

}

}

Of course, anything at a high enough viewpoint looks easy. This representation's simplicity, however, gives a good starting point to tackle the complexity behind making a game engine. This post explores the burgeoning of making pixels show up on the screen.

I chose to start at the SDL3 level of abstraction with regard to graphics programming. This lets me concentrate on the general concepts of programming for the GPU instead of having to learn specific vendor APIs. SDL3 is a C library, but Odin has seamless support for it via the bindings in the vendor library. Although SDL3 gives you a unified language to talk to low level devices, the programmer has the responsibility to connect everything together.

The basic implementation of this ends up to a single Odin file with 438 lines of legible code and lets me push 2D textures to the game window.

Building

The rest of the iceberg of game engines: tooling and building. To make this work, I implemented a straightforward build pipeline. Each step is a simple bash script, orchestrated with mise. At the end of the pipeline, the compiled version of each asset class for the final executable lives next to their source. The final step builds the Odin project and packages everything into the target folder.

project_src

| assets

| | textures

| | | source

| | | compiled

| | shaders

| | | source

| | | compiled

| | { ... }

| target

| | release

| | | executable

| | | assets

| { code and other files }

Tooling

As I want to keep the bash scripts at most a screen full, and only for OS related operations, the logic and complexity resides in single purpose tools. The texture packing step uses cram. Shader compilation uses shadercross. Cram generates a single image with a json metadata file from all the singular images of a directory. The metadata is then read by the first tool I implemented: assetgen. A cli that outputs Odin source code to uses the assets in a programmatic, statically typed way. It is, of course, implemented in Odin.

import items "res:items"

main :: proc() {

// { ... }

draw(items.scraps)

// { ... }

}

package items

// THIS FILE IS GENERATED

// DO NOT EDIT

// { ... }

scraps :: Sprite {

w = 360,

h = 396,

tex_u = 0.3984375,

tex_v = 0,

tex_w = 0.3515625,

tex_h = 0.7734375,

}

// { ... }

Dependency Management

Odin has no package manager, by design. It forces me to take great care in keeping the dependencies at a minimum. I have only a handful so far:

build dependencies

- cram

- shadercross

- Odin toolchain

runtime dependencies

- sdl3

libraries

- clodin, as baseline cli argument parsing

- sdl3, in the Odin vendor repository that ships with the compiler

I only use open source dependencies and I keep a pull mirror of each in case the original repository disappear.

Next Steps

Many things to do. I would be surprised if the next thing I am doing is not input handling.

A Bunch of Links

- books read

- web resources used

- misc tools